It becomes increasingly obvious each day that the smallest social cell is not the family but the individual. And art, in some way, must reflect this phenomenon. To demonstrate, let us, for example, take the case of architecture.

But before we begin to look at the symptomatic work chosen, Taller de Arquitectura’s Walden 7, let us remember that the social and cultural process of individualism is traced far back in history. It was born in twelfth-century Europe with the appearance of towns in Italy.

From that epoch onward, as a result of the Reformation, the Renaissance, industrialization and the rise of the bourgeoisie, social and class traditions have continued to fragment and atomize, right down to the unit of the single individual.

In the Middle Ages, man was born into a world that was organized and organic, his life structured in advance by tradition. It was possible to foresee one’s whole way of thinking, including one’s behavior, within the bounds of the church and the fief.

The cities, in contrast, obliged man for the first time to think and get by on his own, since he founded there none of the sure rules imparted by tradition. And, as the world has expanded, it has become more difficult for the individual in his particular context to find a vision of the world, and a law which is communal rather than individualistic.

Just as the nineteenth century saw the breakup of the family clan, the period since the French Revolution has witnessed the transformation of the individual into the primary social unit.

But that is only the theoretical formulation. For the bourgeoisie, which appears to uphold individualism, strongly adheres to the idea of the family, or rather to what remains of that word’s previous significance. In any case, the only true individuals within the family are the fathers; it is quite a different story for women and adolescents, not to mention children and colonized peoples.

Nowadays, individualism is not only a theory, it is a fact. And it is exactly now that we are beginning to feel it as a realty.

The slow but effective and inevitable revolution of women and others is gradually converting the society of the family into a population of individuals. Of course, the family still has considerable force and cohesion, but this grows less with each passing day. Couples with two jobs or careers, free unions, sons and daughters becoming independent earlier and earlier, working or studying far from their family – all these tendencies, which before were accidental, are now becoming increasingly normative.

But what sort of architecture, what kind of housing corresponds to this individualized society?

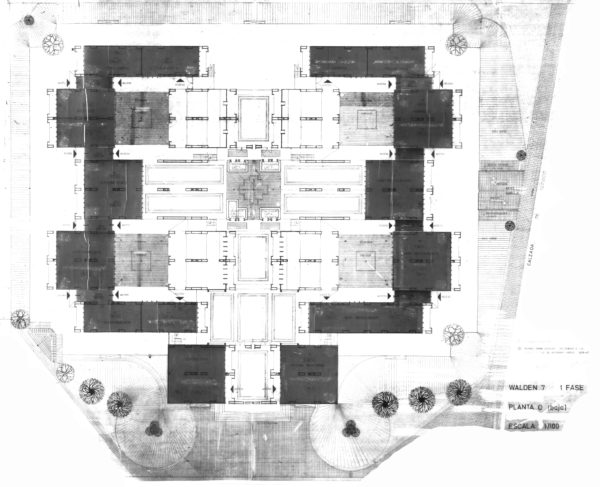

A visit to Walden 7 gives us the opportunity to see a manner of architecture – and here we are dealing with true architecture and authentic art – which has rendered this individualist trend in clearly radical fashion. Radical because it incorporates the basic sociological facts referred to above and provide them with a formal solution. Walden 7 is an urban, architectonic complex located in the former Sanson cement factory. It comprises three gigantic buildings, of which only one is finished, that form the sides of a hypothetical triangle, inside which there still remain a few installations from the former factory.

Two sides of the triangle are formed by low, elongated buildings (the basements of which contain the passageways), which link the large blocks. The space inside the triangle and surrounding the buildings are green areas. In order to understand the phenomenon that interests us, we must confine ourselves to the part of the project that has already been built and which can be visited.

This is the first of the gigantic, approximately 60 meter high blocks, whose form may be evoked by the image of several oval bodies squashed together vertically.

If we look at a photograph of the building, we soon observe that these ovals are wider at their centers than at their extremities and that the exteriors of the apartments resemble somewhat the cells of a hive.

In the interior, we see at once that all the cells differ from one another. Not only does each have its own entrance, but it is also assembled in a different way. In other words, it is not a question of dividing up a large building into apartments after the fact, as in the traditional manner, but of creating a series of individual cells which form a block when put together. As if the architect – which in fact is more or less the case – has taken wooden building blocks and assembled them above and beside one other in order to obtain an organized unit while still maintaining their independence.

In Europe, America and Japan, many single-unit apartment buildings are constructed with the view that the phenomenon of people living and working alone is in fact a permanent one, whereas, in the past, and still occasionally today, such people were considered transient and had recourse only to hotels, hostels and rented rooms.

This problem, which is the result of certain limitations and constraints, has been resolved by Walden 7 in two ways: sociologically, by the provision of an individual “cell” for each person, and formally, by being based on a new global architecture, which will be discussed later.

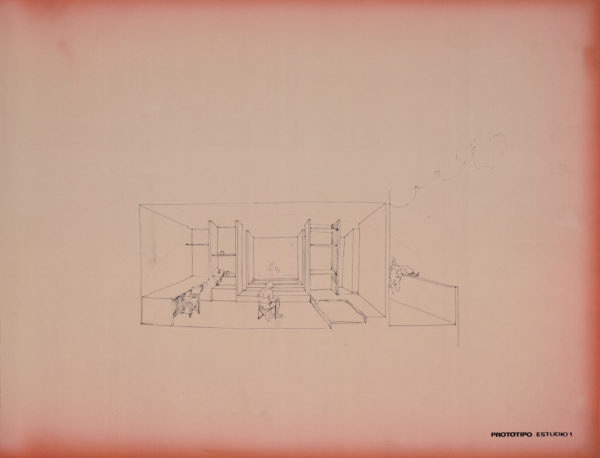

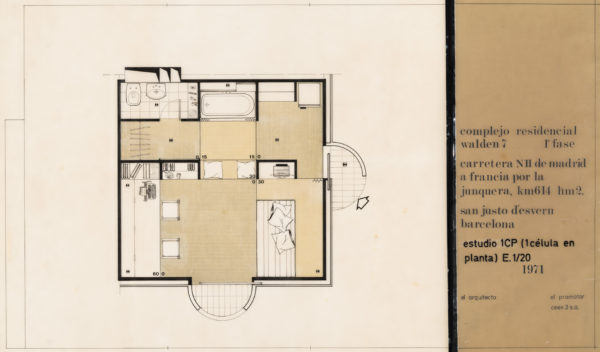

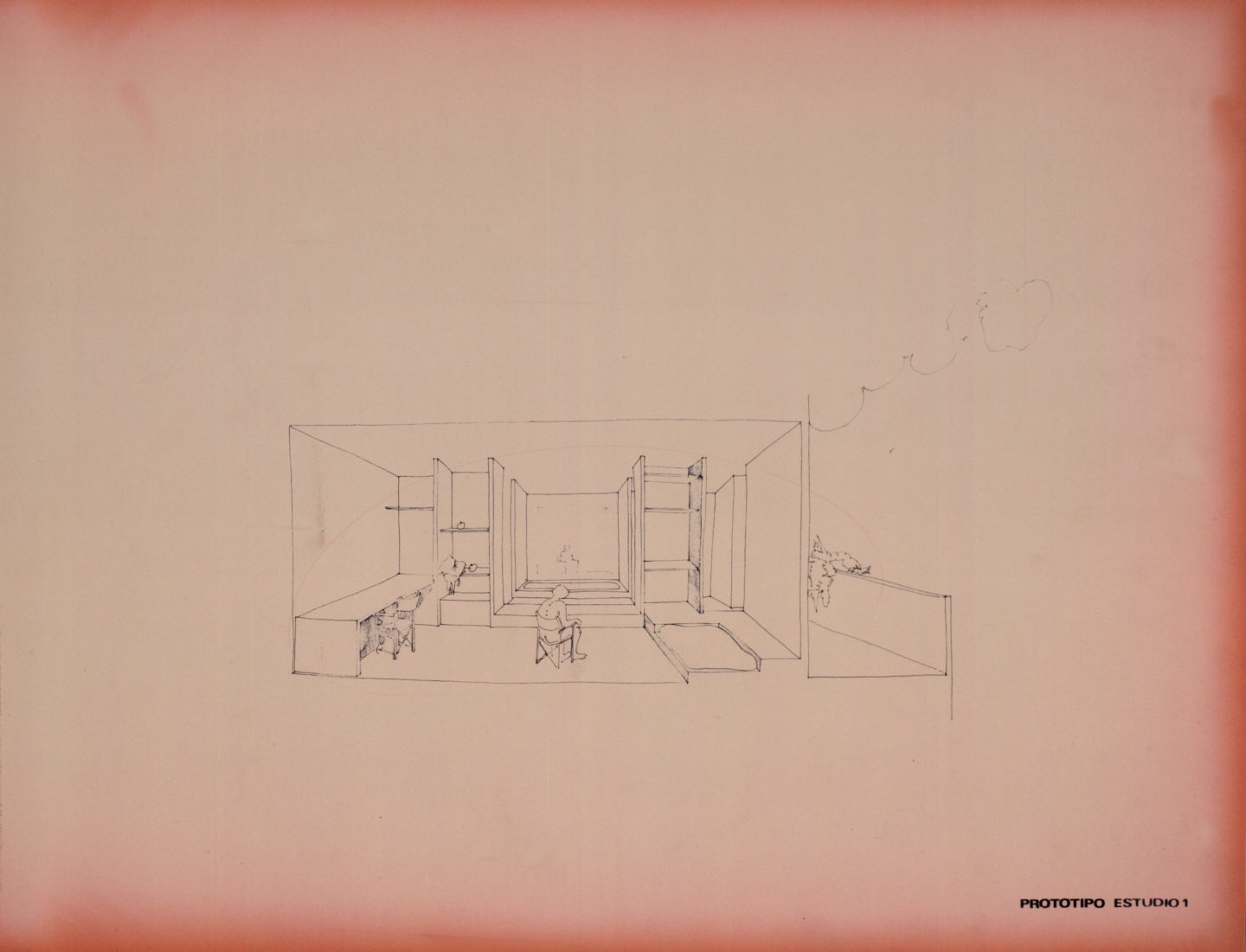

Each cell must answer to the particular needs of the individual occupants. For this reason, the cell is simply a room 30 meters square, which is theoretically empty but in fact only so if the buyer desires it to be. Generally, there is a minuscule kitchen, a wash basin, a toilet, a bath, a table and various cupboards.

The divisions within the cell do not really form rooms; they create a sense of separation. This is clearly not the result of reducing a traditional apartment to an individual one, but of a modern conversion of a rented room to cater to essential needs. All is visible: the kitchen, the bath, the bed, the table. Curtains may be used to screen certain areas, such as in the bath to prevent water from splashing on the floor. However, the clearest evidence that Walden 7 was conceived on an individual and not a family basis is that a family wishing to live there would have to combine one, two, three or four cells horizontally or vertically, on two levels.

For the Taller de Arquitectura, then, the family is not the orange from which one takes a segment, but rather the cluster of individual grapes which form a bunch.

The family may follow either the traditional way, allotting each cell a function, or the line taken by Bofill’s architecture, respecting the individual cell and rejecting compartmentalization. Yet neither the theory not the practice of individualization can end here.

The typical society of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries has provided structures of varying rigidity for small families living in apartments, creating states of either relative harmony or conflict with their neighbors. This competitive situation, which has been aggravated by the process of individualization, will inevitably be revealed ones it becomes necessary to combine the interests of thee private individual with those of the community.

This is what can be seen with varying degrees of clarity at Walden 7. Thus, this is not only a bunch of grapes, but also a communal hive. This is what is suggested by the complicated network of footbridges linking each floor of the building, whose function is in fact clearer in the other Taller de Arquitectura project, The City in Space.

The same applies to the conservation of the factory exterior, which was undertaken in homage both to the past and to the work which has enabled the creation of the present, and in order to readapt those factory installations which remain intact for community facilities.

Walden 7 is not, however, a community of neighbors, even if one day such a community does develop. It is not a utopia, although the medium-rent cells are not too costly. No doubt Walden 7 shows a clear path to that point on the horizon, more or less distant, where, in a capitalist country, the reality of the individual may encounter the utopia of the community. No one can be unaware, when they see the admirable innovations in this work, of what could be if neither property speculation nor any of the economic and legal shackles which hinder the free development of life and art existed.

José María Carandell

November 1974